- 100% of students’ hands in the air

- 100% of kids tracking the speaker

- 100% of the time

In classrooms where students are trained to “track the speaker,” we often hear teachers reminding students that “All eyes should be on the speaker.” Tracking the speaker is a common expectation in urban classrooms, where we are concerned that a lack of student engagement results in low achievement.

In classrooms where students are trained to “track the speaker,” we often hear teachers reminding students that “All eyes should be on the speaker.” Tracking the speaker is a common expectation in urban classrooms, where we are concerned that a lack of student engagement results in low achievement.

No one would disagree that increasing student engagement is important to increasing learning outcomes in American classrooms. We all want 100% of our students to be engaged in their learning and paying attention to what is going on around them in class.

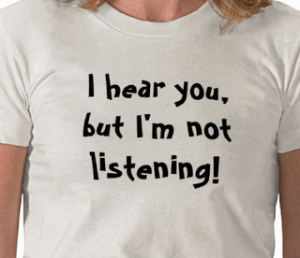

But we question that tracking the speaker automatically translates into increased engagement and the kind of active listening that is central to inquiry-based learning.

In a high-quality classroom discussion, students’ answers build off of other students’ responses, and there is a fluidity to the growth of collective meaning-making that is only possible when students are actively listening and truly tuned in to what their classmates are saying.

Sometimes, however, when a student’s hand goes up, his thinking gets locked in to the answer that he originally raised his hand to convey. If a student’s thinking gets locked in at that place where his hand went up, then that answer may be “out of sync” with where the discussion is in the present moment…or at the moment when the teacher finally calls on him. How many of you who are teachers have called on a student whose hand is in the air and gotten a response that sounds like, “Umm, I forgot what I was going to say,” or gotten a deer-in-the-headlights stare?

the answer that he originally raised his hand to convey. If a student’s thinking gets locked in at that place where his hand went up, then that answer may be “out of sync” with where the discussion is in the present moment…or at the moment when the teacher finally calls on him. How many of you who are teachers have called on a student whose hand is in the air and gotten a response that sounds like, “Umm, I forgot what I was going to say,” or gotten a deer-in-the-headlights stare?

It is also true that students learn how to fake engagement very quickly. Just because a student is looking at the speaker, it doesn’t mean that she is actually thinking about what her classmate is saying. The simple test of a teacher asking a listening student, “Can you put that into your own words,” will reveal the answer.

It is our job as educators to make sure our students are actively listening and participating in the cognitive work of their classrooms. Strong inquiry-based instruction promotes students’ active listening, while tracking the speaker, though a good first step, may create only the appearance of it.